The day she received the news, Ana María Uriana was teaching a class to twenty children. It was a hot summer day in the arid desert of the Middle Guajira when she heard the news: The Ministry of Education had compensated her for the decade she devoted to teaching by appointing her teacher in the department and her community.

The community school is in Guajira next to one side of the abandoned well and the broken-down solar panels that made it work. Nearby is a herd of goats that serve as an economic livelihood for this population.

There, with two classrooms, a dining room, and a kitchen, students from the primary school and elementary school study. High school students must attend schools outside the community, where indigenous teachers teach classes that deal with ancestral knowledge and Western thought. According to Ana María, although there are 40 students enrolled in total in the first and primary school, between 15 and 30 attend classes daily.

At the school in Koloyosú, a classroom attests to the difficult task of educating in rural Guajira.

Since 2003 Uriana has been teaching full-time. She had previously paired teaching with the care and upbringing of her two children. “An indigenous who is going to support ports his community,” she says. In locations as remote as this, teachers are not usually members of the community itself but are earmarked by educational authorities for a certain number of years, through a government scheme. Their classes are taught inaccessible areas, integrating children from different social groups.

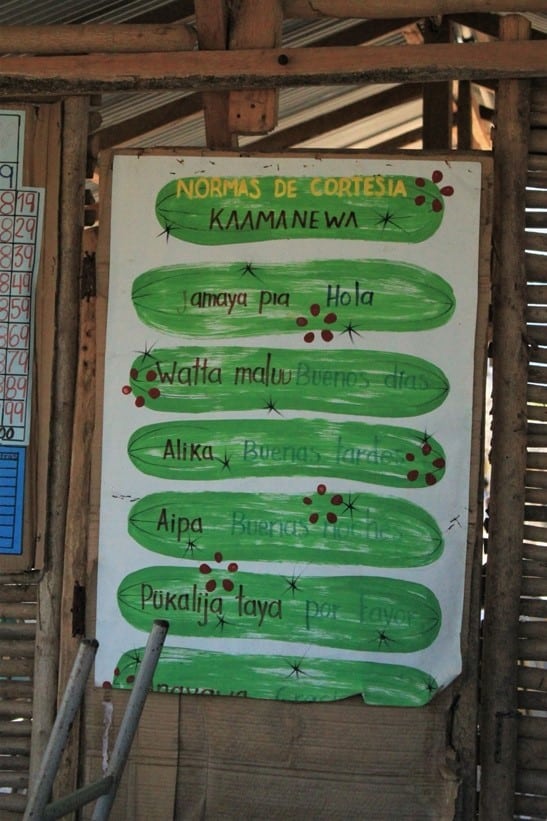

Indeed, all sectors of the community stress the importance of the new generations being able to continue their studies beyond the desert. With this goal in mind, Ana María Uriana promoted bilingual and intercultural education, which aims to combine aspects of the tradition of her indigenous group (mainly the language) with the necessary knowledge to progress in the Columbian educational structure, taking into account the peculiarities of the inhabitants of La Guajira.

Read also: Educate Without Water: The Guajiro Challenge.

A round of questions among the children of the community is sufficient to verify that their expectations, at least in the medium term, go beyond grazing. Several want to emulate football stars, such as James Rodriguez or Radamel Falcao; others are inclined towards vocations that would take them away from this corner of the American continent. Many want to be lawyers, engineers, and doctors.

For 13 years, Ana María has taught her students, traditional education classes, intertwined with subjects in Wayuu training.

Ana Maria regrets that it is still difficult for young people of the different social groups to reach university. “There is discrimination against indigenous people, and the system itself has a share of responsibility,” she says. She, who, at the age of 54, is studying at the university to bring updated content to her classes, states that her children have been the victims of an unequal education for rural and urban inhabitants. His eldest son studied law at The Sergio Arboleda University, Santa Marta, through a loan from ICETEX. Her daughter studies psychology in Riohacha. Both have experienced an unequal education that provides more benefits to students with regular training.

Although in recent years openness to interculturality has been achieved, monolingualism and monoculturalism remain inscribed in the regulations of higher education. For Ana, the solution is not to try to move the educational models of the city to the countryside, but to find a level that gives equal importance to indigenous knowledge and traditional education. “Today, culture, customs are being lost through the evangelization of the school. Children who have left town forget their roots, their tongue. We are rescuing them through 4 subjects that work and are taught on a par with the basic subjects: worldview rather than religion; arts and games, in which she energizes herself with traditional games and the use of musical instruments; wayuunaiki, where we teach language, its speech, and writing; and Wayuu development, which includes knowledge in grazing, animal care, and feeding,” she adds.

It also expresses that indigenous education is a privilege for teachers. “Thanks to it, we can contemplate the magic of learning indigenous worldviews,” she says. For example, she believes that native languages should remain because they are a way of expressing thoughts. “Indigenous groups have a way of learning and conquering the world, their way of thinking and seeing life is based on values, traditions, culture, and perhaps the biggest example is linguistics and crafts,” she emphasizes.

For her, indigenous crafts are “items that are part of ours and that identify us.” At school, she teaches her students about the origin of art and the indigenous stories related to different art pieces.

For the children of the community, Ana is an endearing and unforgettable being. She deserves admiration for the fundamental role she plays in her formation and the permanence of indigenous culture and cosmogony on the human face. She is a responsible, dedicated, professional person and, above all, loving and respectful for the knowledge of indigenous peoples. Above all, she is a teacher committed to her profession and the constant need to develop her skills and knowledge to share with her students the best of herself.